Web Crawler--Wikipedia

As Edwards et al. noted, "Given that the bandwidth for conducting crawls is neither infinite nor free, it is becoming essential to crawl the Web in not only a scalable, but efficient way, if some reasonable measure of quality of freshness is to be maintained." A crawler must carefully choose at each setp which pages to visit next.

The behavior of a Web crawler is the outcome of a combination of policies:

- a selection policy that states which pages to download,

- a re-visit policy that states when to check for changes to the pages,

- a politness policy that states how avoid overloading Web sites, and

- a parallelization policy that states how to coordinate(协调) distributed web crawlers.

Selection policy

As a crawler always downloads just a fraction of the Web pages, it is highly desirable that the downloaded fraction contains the most relevant pages and not just a random sample of the Web.

This requires a metric of importance for prioritizing Web pages. The importance of a page is a function of its intrinsic quality, its popularity in terms of links or visits, and even of its URL(the latter is the case of vertical search engines restricted to a single top-level domain, or search engines restricted to a fixed Web site).

Restricting followed links

A crawler may only want to seek out HTML pages and avoid all other MIME types. In order to request only HTML resources, a crawler may make an HTTP HEAD request to determine a Web resource's MIME type before requesting the entire resource with a GET request. To avoid making numerous HEAD requests, a crawler may examine the URL and only request a resource if the URL ends with certain characters such as .html, .htm, .asp, .aspx, .php, .jsp, .jspx or a slash. This strategy may cause numerous HTML Web resources to be unintentionally skipped.

URL normalization

Crawlers usually perform some type of URL normalization in order to avoid crawling the same ersource more than once. The term URL normalization, also called URL cannonicalization, refers to the process of modifying and standardizing a URL in a consistent manner. There are several types of normalization that may be performed including conversion of URLs to lowercase, removal of "." and ".." segments, and adding trailing slashes to the non-empty path component.

Re-visit policy

The Web has a very dynamic nature, and crawling a fraction of the Web can take weeks or months. By the time a Web crawler has finished its crawl, many events could have happend, including creations, updates and deletions. From the search engine's point of view, there is a cost associated with not detecting an event, and thus having an outdated copy of a resource. The most-used cost functions are freshness and age.

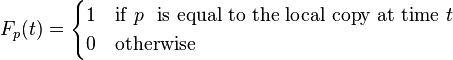

Freshness: This is a binary measure that indicates whether the local copy is accurate or not. The freshness of a page p in the repository at time t is defined as:

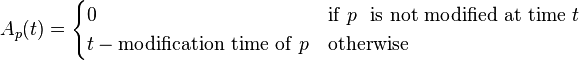

Age: This is a measure that indicates how outdated the local copy is. The age of a page p in the repository, at time t is defined as:

The objective of the crawler is to keep the average freshness of pages in its collection as high as possible, or to keep the average age of pages as low as possible. These objectives are not equivalent: in the first case, the crawler is just concerned with how many pages are out-dated, while in the second case, the crawler is concerned with how old the local copies of pages are.

Tow simple re-visiting policies were studied by Cho and Garcia-Molina:

Unifom(均匀的) policy: This involes re-visiting all pages in the collection with the same frequency, regardless of their rates of change.

Proportional(成比例的) policy: This involves re-visiting more often the pages that change more frequently. The visiting frequency is directly proportional to the (estimated) change frequency.

(In both cases, the repeated crawling order of pages can be done either in a random or a fixed order.)

Cho and Garcia-Molina proved the surprising result that, in terms of average freshness, the uniform policy outperforms the propotional policy in both a simulated Web and a real Web crawl. Intuitively(凭直觉), the reasoning is that, as web crawlers have a limit to how many pages they can crawl in a given time frame, (1)they will allocate too many new crawls to rapidly changing pages at the expense of less frequently updating pages, and (2) the freshness of rapidly changing pages lasts for shorter period than that of less frequently changing pages. In other word, a proportional policy allocates more resources to crawling frequently updating pages, but experiences less overall freshness time from them.

To improve freshness, the crawler should penalize the elements that change too often. The optimal re-visiting policy is neither the uniform policy nor the proportional policy. The optimal method for keeping average freshness high includes ignoring the pages that change too often, and the optimal for keeping average age low is to use access(存取) frequencies that monotonically(单调地) (and sub-linearly(线性地)) increase with the rate of change of each page. In both cases, the optimal is closer to the uniform policy than to the proportional policy: as Coffman et al. note, "in order to minimize the expected obsolescence time, the accesses to any particular page should be kept as evenly spaced as possible". Explicit formulas for the re-visit policy are not attainable in general, but they are obtained numerically, as they depend on the distribution(分发) of page changes. Cho an Garcia-Molina show that the exponential(越来越快的) distribution is a good fit for describing page changes, while Ipeirotis et al. show how to use statistical tools to discover parameters that affect this distribution. Note that the re-visiting policies considered here regard(看待) all pages as homogeneous(同质的)in terms of quality ("all pages on the Web are worth the same"), something that is not a realistic scenario, so further information about the Web page quality should be included to achieve a better crawling policy.

Politeness policy

Crawlers can retrieve data much quicker and in greater depth than human searchers, so they can have a crippling(严重破坏) impact on the performance of a site. Needless to say, if a single crawler is performing multiple requests per second and/or downloading large files, a server would have a hard time keeping up with requests from multiple crawlers.

As noted by Koster, the use of Web crawlers is useful for a number of tasks, but comes with a price for the general community. The costs of using Web crawlers include:

- network resources, as crawlers require considerable(相当大的) bandwidth and operate with a high degree of parallelism during a long period of time;

- server overload, especially if the frequency of accesses to a given server is too high;

- poorly(糟糕地) written crawlers, which can crash servers or routers, or which download pages they cannot handle; and

- personal crawlers that, if deployed by too many users, can disrupt networks and Web servers.

robots.txt protocol that is a standard for administrators to indicate which parts of their Web servers should not be accessed by crawlers.

Architectures

A crawler must not noly have a good crawling strategy, as noted in the previous sections, but it should also have a highly optimized architecture. Shkapenyuk and Suel noted that:

While it is fairly easy to build a slow crawler that downloaders a few pages per second for a short period of time, building a high-performance system that can download hundreds of millions of pages over several weeks presents(带来) a number of challenges in system design, I/O and network efficiency, and robustness and manageability.

Example

PolyBot: A high-Performance Distributed Web Crawler

High-Performance Web Crawling -- Marc Najork, Allan Heydon September 26, 2011

Abstract

...For example, search services use web crawlers to populate their indices, comparison shopping engines use them to collect porduct and pricing information from online vendors, and the Internet Archive uses them to record a history of the Internet. The design of a high-performance crawler poses many challenges, both technical and social, primarily due to the large scale of the web. The web crawler must be able to download pages at a very high rate, yet it must not oberwhelm any particular web server. Moreover, it must maintain data structures far too large to fit in main memory, yet it must be able to access and update them efficiently.

Introduction

Although the web crawling algorithm is conceptually simple, designing a high-performance web crawler comparable to the ones used by the major search engines is a complex endeavor(事业).

Mercator:

- Distributed

- Scalable

- High Performance

- Polite

- Continuous

- Extensible

- Portable(written in Java)

There is a natural tension between the high performance requirement on the one hand, and the scalability, politeness, extensibility, and portability requirements on the other. Simultaneously supporting all of these features is a significant design and engineering challenge.

A survey of Web Crawlers

Web crawlers are almost as old as the web itself.

- Google Crawler: The original google crawler (developed at Stanford) consisted of five functional components runing in different processes. A URL server process read URLs out of a file and forwarded them to multiple crawler processes. Each crawler process ran on a different machine, was single-threaded, and used asynchronous I/O to fetch data from up to 300 web servers in parallel. The crawlers transmitted downloaded pages to a single StoreServer process, which compressed the pages and stored them to disk. The pages were then read back from disk by an index process, which extracted links from HTML pages and saved them to a different disk file. A URL resolver process read the link file, derelativized the URLs contained therein, and saved the absolute URLs to the disk file that was read by the URL server.

- Internet Archive: The IA also used multiple machines to crawl the web. Each crawler process was assigned up to 64 sites to crawl, and no site was assigned to more than one crawler. Each single-threaded crawler process read a list of seed URLs for its assigned sites from disk into per-site queues, and then used asynchronous I/O to fetch pages from these queues in parallel. Once a page was downloaded, the crawler extracted the links contained in it. If a link referred to the site of the page it was contained in, it was added to the appropriate site queue; otherwise it was logged to disk. Periodically, a batch process merged these logged "cross-site" URLs into the site-specific seed sets, filtering out duplicates in the process.

Merctor's Architecture

The basic algorithm requires a number of functional components:

- a component (called the URL frontier) for storing the list of URLs to download;

- a component for resolving host names into IP address;

- a component for downloading documents using the HTTP protocol;

- a component for extracting links from HTML documents; and

- a component fro determining whether a URL has been encountered before.

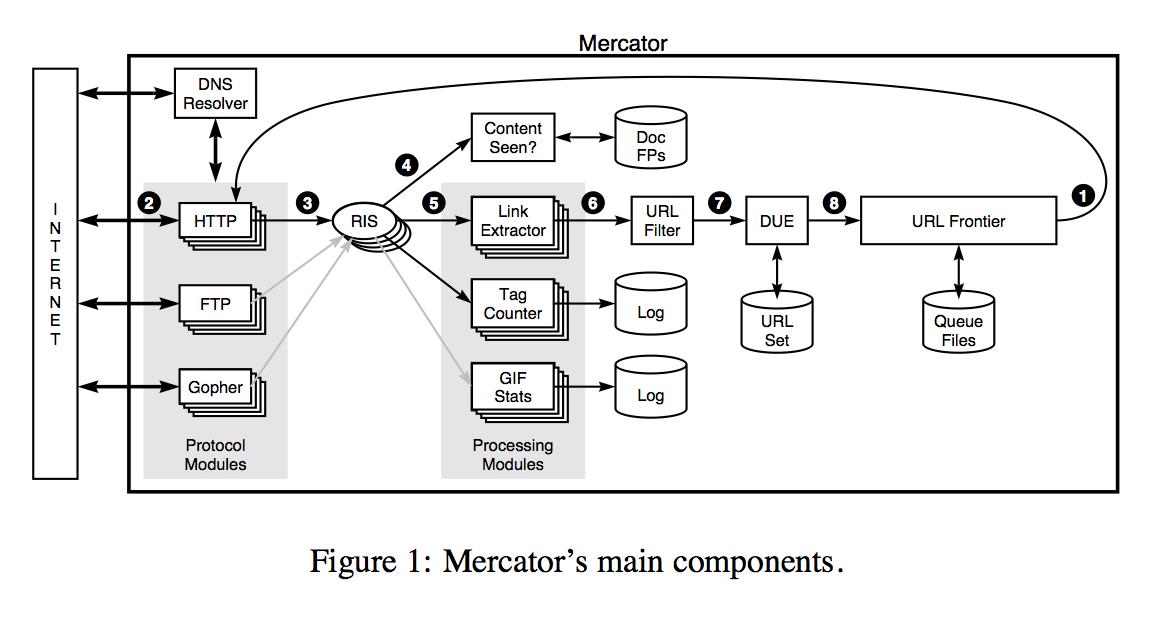

To avoid downloading this resource on every request, Mercator's HTTP Protocol module maintains a fixed-sized cache mapping host names to their robots exclusion rules. Once the document has been written to RIS, the worker thread invokes the content-seen test to determine whether this document with the same content, but a different URL, has been seen before. Every downloaded document has content type. In addition to associating schemes with protocol modules, a Mercator configuration file also associates content types with one or more processing modules. A processing module is an abstraction for processing downloaded documents, for instance:

- extracting links from HTML pages,

- counting the tags found in HTML pages,

- or collecting statistics about GIF images.

Based on the downloaded document's content type, the worker invokes the process method of each processing module associated with that content type. For example, the Link Extractor and Tag Counter processing modules in Figure 1 are used for text/html documents, and the GIF Stats module is used for image/gif documents. By default, a processing module for extracting links is associated with content type text/html. The process method of this module extracts all links from an HTML page. Each link is converted into an absolute URL and tested against a user-supplied URL filter(like RegExp) to determine if it should be downloaded. If the URL passes the filter, it is submitted to the duplicate URL eliminator(DUE), which checks if the URL has been seen before, namely, if it is in the URL frontier or has already been downloaded. If the URL is new, it is added to the frontier. Finally, in the case of continuous crawling, the URL of the document that was just downloaded is also added back to the URL frontier. As noted earlier, a mechanism is required in the continuous crawling case for interleaving(插入) the downloading of new and old URLs. Mercator uses a randomized crawling priority-based scheme for this purpose. A standard configuration for continusus crawling typically uses a frontier implementation that attaches priorities to URLs based on their download history, and whose dequeue method is biased torards higher priority URLs. Both the degree of gias and algorithm for computing URL priorities are pluggable components. In one of our configurations, the priority of documents that do not change from one download to the next decreases over time, thereby causing them to be downloaded less frequently than documents that change often. Checkpointing is an important part of any long-running process such as a web crawl. By checkpointing we mean writing a representation of the crawler's stat to stable storage that, in the event of a failure, is sufficient to allow the crawler to recover its state by reading the checkpoint and to resume crawling from the exact state it was in at the time of the checkpoint. By this definition, in the event of a failure, any work performed after the most recent checkpoint is lost, but none of the work up to most recent checkpoint. In Mercator, the frequency with which the background thread performs a checkpoint is user-configurable; we typically checkpoint anywhere from 1 to 4 times per day. The description so far assumed the case in which all Mercator threads are run in a single process. However, Mercator can be configured as a multi-process distributed system. In this configuration, one process is designated the queen(蜂王), and the others are drones(工蜂).Both the queen and the drones run worker threads, but only the queen runs a background thread responsible for logging statistics, terminatiing the crawl, and initiating checkpoints. In its distributed configuration, the space of host names is partitioned among the queen and drone processes. Each process is responsible only for the subset of host names assigned to it. Hence the central data structures of each crawling process -- the URL frontier, the URL set maintained by the DUE, the DNS cache, etc. -- contain data only for its hosts. Put differently, the state of a Mercator crawl is fully partitioned across the queen and drone processes; there is no replication of data. In a distributed crawl, when a Link Extractor extracts a URL from a downloaded page, that URL is passed through the URL Filter, into a host splitter component. This component checks if the URL's host name is assigned to this process or not. Those that are assigned to this process are passed on to the DUE; the others are routed to the appropriate peer process, where it is then passed to that process's DUE component. Since about 80% of links are relative, the vast majority of discovered URLs remain local to the crawling proecss that discovered them (局部性原理). Moreover, Mercator buffers the outbound URLs so that they may be transmitted in batches for efficiency (批量转发). Figure 2 illustrates this design. Designing data structures that can efficiently handle hundreds of millions of entries poses many engineering challenges. Central to these concerns are the need to balance memeory use and performance.